Marilyn Manson

by Paul Gargano

November 2000

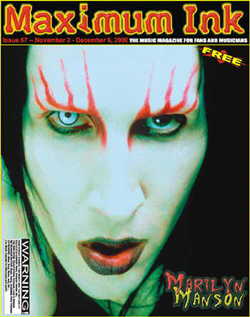

Marilyn Manson on the cover of Maximum Ink in November 2000

Marilyn Manson knows a thing or two about fire and brimstone. His music scorches the earth like flames from the fingertips of an angry God, blazing through anything in its path and pulsing with an industrial-strength rage and heavy metal-inspired bravado, offering the perfect rough-and-tumble accompaniment to vocals that spray from the speakers like a hailstorm unleashed from the heavens, pelting the skin and piercing the psyche. Driven by equal parts rebellious fervor and spiritually charged dogma, he knows no path other than that of the philosophically profound and socially rehabilitative, but to hear his critics offer their take on his rock ‘n’ roll tantrums, he’s a disease in which every one of society’s self-serving watchdogs has a cure. His Portrait Of An American Family debut laid the groundwork for a band that would revolutionize the face of modern music with Antichrist Superstar, a release that gave the American youth a figure to rally behind, and American powers-that-be a figure to rally against. Manson shifted outward gears from religiously tempered to sexually shape-changing with Mechanical Animals, but his message stayed the same within music that took on a more refined and high-polished sheen. He’s been one of the most chronicled artists of the past decade, but consider it all the calm before the storm. Holy Wood (In the Shadow of the Valley of Death) is his outfit’s most ambitious outing yet, swirling their heaviest music to date within a soundscape that turns the hypocrisy of an American culture on end. His physical image is eerie enough to scare his Omega character into submission, and the music has hooks that scrape the skin with an infectious blend of heavy metal thunder and punk rock lightning. Marilyn Manson offered this exclusive look at the vast array of forces that shaped his entertainment Eden Holy Wood and its shadow-filled photo negative Death Valley. Welcome to Holy Wood…

MAXIMUM INK: A lot of people were critical of the direction you took with Mechanical Animals. Is it a coincidence that Holy Wood seems to be a return to your Antichrist form?

MARILYN MANSON: This one’s going to blow a lot of minds! After finishing Antichrist Superstar I knew that I had painted an ending that wasn’t finished. When Mechanical Animals came out, it was just another part of the story, and Holy Wood wound up being the beginning, the glue that ties the three albums together. It makes quite a lot of sense, and people will understand Mechanical Animals in its context, and they’ll understand Antichrist Superstar in its context. In my book—which in my best guess will probably be out in the beginning of next year—the story is explored very detailed and very graphically, even more so than I would have been able to in a movie, so it turns out that I was much happier making it into a book and an album than a film. The film may still be a possibility, it’s just that the subject matter… In some ways I was complimented, because people told me that they all wanted to make a Marilyn Manson movie but when reading the script there wasn’t one thing in particular that they could put their finger on, but they knew it was wrong. They said that the overall tone of the entire thing was just too controversial for them.

MI: Was the script something that had been a work in progress for a while?

MM: Yeah. It was an adaptation of the story, because the story has been laying around in one form or another in short stories, in pieces, things like the hidden track on Mechanical Animals—that was an expert of dialogue—and the end of Antichrist Superstar—“When all of your wishes are granted, many of your dreams are destroyed”—that is the first line of the film in the script and in the book. It was interesting because I was attempting this in a climate where everybody was afraid to do anything because of all of the violence with Woodstock and all, the [Columbine] teen shooting that went down, and a lot of people turned out to be Judases, a lot of people turned their back on me, a lot of people shut doors on me. So when I finished Mechanical Animals I locked myself away for about three months, literally, in my house. I didn’t leave. Part of it was that I could feel the stare, I could feel death outside the door, I could feel people’s hatred and people’s desire to see me go down. Whether that be with just my career, or with realistically killing me, I could feel it. I didn’t have to see it, or hear it in a threat, I could just feel it. It wasn’t something that I was afraid of, instead I just stayed away from it and I submerged myself in making this record. Fortunately, at the end of those three months, I came out—so to speak—with this book and these lyrics, and in the meantime the band had the mission of coming up with ideas for music. And they ended up being more prolific than ever, writing 100 pieces of music. Thirty of them we turned into legitimate songs, and 19 wound up being on the album. It sounds like a lot, but the way that it’s laid out, it’s actually shorter than Antichrist Superstar. There are things that are split in half and have different titles, and it manages to really tell a story and captures a lot of things, but without being an album where you can’t just listen to it. I tried to walk that line because there’s a point where you become self-indulgent. The point where you reach that is when you’re not conscience of your listener. Now, I know as an artists you try to be true to yourself and what you want to do, but you can’t ignore your fans and the people who want to hear this, so you have to either be entertaining, or make it work in a way where it’s not just you doing it for the sake of you doing it. So I think I accomplished making what could have possibly been a pretentious, self-indulgent, art-rock record, but in a way that manages to work. Much like I think I did with the last two.

MI: You talked about feeling a threat. Don’t you think you may have invited a lot of that with your actions? Especially with Antichrist ?

MM: Well, that’s a good question. With Antichrist Superstar I was really attacking the mainstream and status quo of what is morality and what religion stands for, and that’s a fight that I’m always willing to be a part of. But the other situation that happened at the end of ‘99 [Columbine] was me being accused of something I wasn’t responsible for, and that I wasn’t even associated with in the end. And it wasn’t my battle to fight, and it’s wasn’t something you can defend. It wasn’t like I could say, “Hey, I’m right and here’s why.” There were a lot of emotions involved and there were a lot of people who wanted to find one person to blame for something that they couldn’t understand. Like when Kennedy died, they wanted that one Oswald —They wanted to say, “This is the guy who did it. He’s gone now, we could all sleep safely.” They wanted Marilyn Manson to fall for that, and half of it was my image, it works well for their marketing. Because the news, they are just selling fear and I was the trailer, that’s what it came down to. It got to the point where I found a lawyer and I said, “If my name is blamed or mentioned with this incident, I’m going sue you.” And most of them backed off because they didn’t have a legitimate reason to be doing this. So I wanted away from the world, and I didn’t want to watch it in the news, and I didn’t want to be the one being blamed for it of it… You know, I was watching TV when Columbine happened, and I said, “I know I’m going to get blamed for this.” And they just really ran with it.

MI: So Holy Wood was written as a response?

MM: With Holy Wood, when you hear this you’ll understand—What I’ve done is not only finish the story that I started, but to analyze and question the evolution of mankind and where it’s going. The idea that humans are predestined to destroy themselves, and what can you as a listener do to change that, what can you do to make that stop? The story, to break it down simply, is about an innocent—much like Adam in the Garden of Eden—who, if ignorance were bliss, would have the opportunity to just live his life and never want anything different. But in my story, I’ve created these two metaphorical places—one being Death Valley, and one being Holy Wood—and Death Valley is where the disenfranchised, the unwanted and the imperfect are, and Holy Wood is where everything that is held up as being great and perfect exists. And the main character—which it isn’t fair to call it a character, because it’s so autobiographical—wants to be a part of that bigger world, wants to fit in, and thinks that they could make that work, so tries and tries their entire life to become a part of something they think is right, the world of “Coma White,” the world of everything that he’s obsessed with, that he thinks will make him happier. And when he gets there, he realizes that the people in this world where the grass is greener are the people that treated him like the weed and that manifests itself as such a bitter resentment that he tries to create a revolution. He is so naive and idealistic that he thinks, “I can change this.” Any revolutionary thinks they can change the world, and what happens is, his revolution—while it starts out strong—becomes another product. That is what I was trying to say with the character Omega, sort of a hollow representation of the sarcastic version of me. And on Mechanical Animals, the other seven songs from Omega’s perceptive are more of the internal feelings of what’s going on. In the storyline, by the time he realizes that he’s been sold out, he’s sold his soul to the wrong person. He’s become everything that he’s always tried to fight against, it’s too late, and he knows the only answer of how to stop this is to destroy himself, and that’s Antichrist Superstar.

MI: Did this whole concept start as an idea you had, or is it reality based?

MM: While coming up with the idea, I found that the basic story is so similar to Jesus Christ. For example, one could look at him as a revolutionary, someone who had all these radical ideas, and what they did was take his teachings and turned them into something on someone’s wall—the crucifix being the greatest mass marketing thing ever created in the history of mankind—and he ultimately sacrificed himself for it. I started to think about that story in a different way, and I stared to think about the martyrs, and I started thinking about the ideas of entertainment being blamed for violence. I started to think about when I was born—This record has a lot of references to the feelings and the climate of the late-‘60s. 1969 ended darkly with Altamont and the Manson murders, in the same way that ‘99 did with Columbine and Woodstock. They were very similar, it is amazing. So I started think about the idea of martyrdom—Is there anything darker than some of the stories that are in the Bible? Is there an image that’s more sexual and violent than the crucifixion of Christ ? You’ve got a bleeding, half-naked, dying man, who in essence has, in one way or another, committed suicide, martyred himself. And then films—Growing up we all watched the Zapruder film [The J F K assassination footage ]on TV all the time, which is more graphic and devastating and shocking than anything any filmmaker could dream up. There was the most important director of our time, and he didn’t even know it, it’s just by default. So I started finding these correlations, and I started to layer the album with coincidences and correlations that at times even sound paranoid or conspiracy-originated. This was… I wouldn’t say difficult, but it was a very trying album to make. But also a very rewarding one, because we all felt that we were a part something very important—Not just as a band, that this is our album and we want it to sell, as much as that we have something that’s very important to say, and it’s essential because nobody has the balls to stand up for it.

MI: Do you think that people will take this album for what it’s intended to be, or do you think they’ll just write it off as Marilyn Manson trying to make waves again?

MM: I don’t find that to be a concern to me. It’s created because I needed to do it, and for the fans. The critic and the fan are two different things, they listen to music for different reason, and I’m not concerned in that sense. I think people will find more than they expect on this record, and I think that this record takes it to a point where I can’t even image where I will go next.

MI: You wrote a piece for Rolling Stone in response to the accusations directed at you after Columbine. It’s been awhile since a musician has been articulate enough to stand up and fight the establishment. Was that ever your intention, or was that piece just written in self-defense?

MM: I wanted to tell everyone that I think mankind is violent by nature, and there was no point in attacking anyone in particular. I genuinely feel sorry for everybody involved, including the two kids that did it—everybody suffered, and for different reasons. I think America needs—and is waiting for—someone to give them some sense of spirituality, something to believe in. We’ve lost anything to believe in. When we grew up, we always had wars to fight, there was always an enemy. There was the cold war, or the Vietnam War. We always had a bad guy, so you knew what to believe in. Communism is bad, let’s destroy them. Now the only enemy that people can find is entertainment, and I think it’s only going to get worse. That’s why I take a stand and come out swinging right off the bat with this record. If the conservatives and the politicians and the censors are going to attack this, I’m prepared to fight.

MI: Is the album’s release intended to correspond with Election Day?

MM: Well, the release date is still fluctuating, but it looks like it may be Election Day, actually. I’m happy with that, because October is really cluttered [with other album releases]... The album could have come out in September— I won’t get into the reasons why, but we were ready to go. It actually works very well considering the subject matter I speak a lot about on the album. I wasn’t planning that as some sort of gimmick, but it looks like it’s worked out that way.

MI: Are you going to be voting in this election?

MM: No. I refuse to vote, because if I have to align myself with any party, I’d come closest to a Libertarian, but I don’t think I can call myself anything. Once again, it’s just another campaign for selling fear. That’s the way it’s always been, I wasn’t surprised, upset, or in disbelief—It’s always been bullshit to me, and that’s why I refuse to be involved in it, and I just go around it.

MI: Around it, and sometimes you just clash head on!

MM: I expect a lot of flack on this one!

MI: Especially since Al Gore recently said he’d be going back after the entertainment industry, resurrecting Tipper Gore ‘s campaign.

MM: And then there’s Lieberman. Me and him go back a long way, considering I quoted him on the back of my book saying that I’m the sickest act promoted by a major label. That’s a compliment! People are very dangerous, and in particular on a personal level, because they are attacking what I do. The musical climate has changed in so many ways—The metal scene has kind of come back, but not the metal scene as we knew it. The metal scene when we were growing up was very underground. Now it seems that if you’re heavy you are going to get on the radio, and that’s all that really counts. There are a lot of mediocre things that are doing very successfully, and I don’t say that in a jealous way. That’s the reason why Mechanical Animals strayed away from any sort of heavy, angst-laden guilt—One, I wasn’t feeling it and that wasn’t what I wanted to say with the record, and two, it was just such a predictable thing to do. With this album I wanted to combine elements of the previous two, and it works out that way. It’s very difficult for me to be interested in doing heavy songs, because it’s my nature to go against the grain. So on this record, I tried to do heavy songs in a new and ironic way. This record has a lot of dynamics where it’s heavier than anything I’ve ever done and makes the song “Antichrist Superstar” seem like a lullaby, then it’s heavy in a different way—It’s heavy as a piano song, it’s heavy because of its lyrics and its mood. There’s more to being heavy than just going all out, and that’s a tough line to walk. There’s a lot you have to be conscience of.

MI: The music industry is very different than it was when you released Portrait Of An American Family. Does it feel more competitive now? There’s only room on the radio for so many Limp Bizkits, Creeds and Marilyn Mansons.

MM: You know what? It’s evolution and survival of the fittest. You can be ignorant and say, “I’m going to do what I did five years ago, and if they don’t like it, too bad, because that’s what I do.” Or you can look at what’s happening and you can say, “You know what? That is a lame attempt at doing what I’m capable of doing, so I’m going to do something 100 times better and teach you how it’s done, because I was there when your were still trying to learn how to play guitar.” So there’s a bit of vengeance on the album, and it’s definitely not a sense of what I know a lot of critics are going to have the inclination to do, saying that the glam attempt was a failure—which it wasn’t—and that Manson is trying to regain his roots, because I’m not. This record does not sound like either of the past two, but it’s an evolution of both of them. As an artist, the writing process turned out to be really good and very prolific in that Twiggy [Ramirez] and John 5 are very opposite in the way they write, and the album turned out that I wrote a song with John from beginning to end, and then Twiggy and I would drink Absinthe and go into the desert with a micro-cassette and come back not remembering what we did, operating on a subconscious level because we let our mind go on auto-pilot, which is something we normally wouldn’t do. Where as with John we would write in a more conventional manner, it’s a great balance. I think the band feels like a band to everybody, and it sounds like a band. That’s one of the great things about this one, it really brought us together.

MI: There seems to be less emphasis on “bands” today, and more emphasis on characters? Do you find that distracting from the music?

MM: Well, we are in a really fucked up time for music, and I can’t say that that doesn’t remind me of 1990, because it does in that things are moving faster and the attention span is getting shorter. So we are in a time where you have to adapt or be destroyed, and music is… I’m hoping that because there is an abundance of good and bad—mostly bad—that it’s going to make people sick. It’s like when you eat too much. I think, hopefully, it will make things better, but chances are it won’t. The industry is based on this week’s sales and if your single is a hit, and I’m one of the few remaining career artists out there. Many of them have disappeared —Smashing Pumpkins, Nine Inch Nails ’ future is in question… It’s very difficult now to be what music was always about in the beginning. Not to say that record labels really cared about what you did, but music was appreciated a little bit differently when we were growing up. But we may be able to regain that. I’ve gone out of my way—I mean, the artwork on this record took as much effort as making the music itself. I made it as vivid and as interesting on every level as possible, just because I like it that way, and to set the standard.

MI: For us, growing up, arena shows were the norm, but not anymore. Do you think there’s room for arena rock today? Bands that go platinum are still only playing clubs. Will we have arena rock stars again?

MM: It depends on how many cattle you want to shove into a building or how many fans you what to put into a building. I think there was an attempt—much like in my story—in the business environment to try to push Marilyn Manson into a hole where they didn’t fit. The Mechanical Animals tour had a lot of stigmas attached to it—Whether it was the combination of Hole, or any one thing after another that was very trying. I earned a lot of character. And with this one, I’m looking at it the same way that I always have. The fortunate thing is that it doesn’t matter if we have a hit song on the radio, because we have such a loyal fan base that we can go tour—In any part of the world, not just in America. That’s something that you can’t get overnight, and that’s something that with the combination of fans’ loyalty and us always just working hard you can keep. You can’t just start at the top and try to learn that.

MI: Are you taking that approach with Godhead, the first band on your Posthuman label?

MM: Well, I tried to share with them my bit of knowledge, and they have already started to build a following, which is great, and that was one of the main reasons. I think their record came out great, and I chose a home in Priority because they’ve been a place that will always stand behind their records. Records that no one would put out. And I’m not looking to find bands are going to sell, I’d rather support someone that’s doing something out of the ordinary. In no way is it a vanity label, and I’m not going to sign a bunch of bands and buy everything I can get involved in.

MI: When is their album due?

MM: Early next year, and I think they are going to do our tour at the very end of October, right before Halloween. It’ll be an extensive American tour, big in the sense that I can appreciate the fact that couple-thousand seat places are big. We’re going to stick to places that sound better, and places where people can really enjoy us. The thing I dislike most about arenas is, we’re the type of band that can really be appreciated when there’s an intimacy. We’re not scaling down by any means, and believe me when I say it’s not a cop-out because I don’t think we can sell more tickets. I just think it’s right for this record and how I want it to be heard. The tour will last throughout the year, then we’ll try to get together with someone more appropriate.

MI: Despite the publicity that surrounded your tour with Hole, you’ve really stayed out of the tabloids when it comes to conflicts with other artists. How have you managed steering clear of the Fred Durst/Scott Stapp fiascoes?

MM: If I have a distaste for someone, I’ve got no reason to waste my space in a magazine talking about them, it doesn’t really accomplish anything. With Courtney [Love] it was entertaining because I was just being a dick because she deserved it, and she still does! With anything else, if it’s a personal thing I have no reason to talk about it. If it’s an opinion, then most of the time it just comes off sounding bitter, or envious, or high school. I’m not going to take a pot shot at Fred Durst —I mean, find a reason not to! My reason not to is because I just don’t feel like wasting my time. It’s obvious—Why take a shot at him when you’re just stating something that everyone knows? Whatever, I don’t give a fuck about him, he can do whatever he does.

MI: You’ve filled the role or rock star and role model. Do you think we need more of one instead of the other today?

MM: There are a lot of people living the rock star thing, but it’s in rap. I was talking with someone earlier today about something that I dealt with a lot on Antichrist Superstar—It goes back to someone having a certain amount of power in their hands. Like Julius Caesar—When you’re up in front of a large group of people, it’s what you do with that power. When it’s in the hands of somebody foolish, then that’s when it can really become dangerous, and that’s when you get your crazy disasters like Woodstock ‘99. People don’t really understand that power, and it comes with really learning the ropes of becoming a rock star. I don’t know if the world needs more rock stars, I think there are plenty of them—Whether they are manufactured or not. I think a lot of them, probably a lot of the people that are on the cover of your magazine, sadly—if you just look at it on a astute or a technical level—are really just in the limelight filling in. They really don’t have the kinds of rock star qualities like the people when we were growing up. Maybe there don’t need to be more, but there need to be different stars. And I’m not saying that I’m different! I’ve already got enough attention in my life!

MI: A lot of your attention has come from your imagery. Do you view the visual as being as important as the music?

MM: If it’s not there, I think it’s being lazy on the artists part. In some instances, maybe the music doesn’t need it, but when writing a song I’ve always got an image in my head. Whenever I start something new, it always affects my personality and the way I look. Particularly on this record, because it’s very cinematic.

MI: Are you amused by all the theories people have about what you’re going to do next?

MM: You know, as long as they are thinking that makes me happy. I’m not trying to provide an answer, I’m just trying to encourage people to find their own. The way that Antichrist found and purged its rage and Mechanical Animals was about discovering emotions, this one is about finding spiritually and examining it. It’s just a dark and different look at spirituality, and not in a way that most would expect.

MI: Did what happened with Columbine make you stop and look at what you were doing as an artist, or did it reinforce what you were doing as an artist?

MM: No, it proved my point. The media’s exploitation of the whole event was exactly what I’ve been saying for 10 years, and the fact that they blamed me was the biggest irony. Holy Wood takes that subject of violence and why mankind behaves the way that it does, and does not pull any punches. It’s not as simple as they think that entertainment is bad, it’s a problem that parents are raising their kids to feel like they are dead already and they have nothing to live for. They are raising their kids to feel like they are not good enough no matter what they do, and it’s only going to get bad results. And that’s why I was saying that this record is important, because people are in need of spirituality of some sort. As an artist it reinforced in me that I had to go out there and make an even more powerful statement that reaches people and makes them feel like somebody else understand the way they feel.

MI: If the music were to stop tomorrow, what would you want Marilyn Manson to be remembered for? What would you want your legacy to be?

MM: I think it’s as simple as narrowing it down to the name Marilyn Manson—Just like when I thought of it and what it represented to me. I think it still stands for everything I believe. That’s a tough question because I’m not done yet, so I don’t put myself in that mindset… But I think that my name says it all.

• Wiki

Marilyn Manson

CD: Holy Wood (In the Shadow of the Valley of Death) Record Label: Nothing

• Purchase Holy Wood (In the Shadow of the Valley of Death) on Amazon

• Download Holy Wood (In the Shadow of the Valley of Death) on Amazon