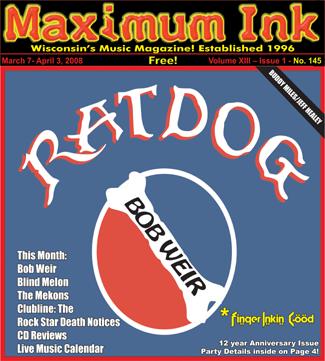

Ratdog

an interview with Bob Weir

by Sarah H. Grant

March 2008

Ratdog featuring Bob Weir on the cover of Maximum Ink in March 2008

Maggot infested skulls on bony blood-dried bodies, skulking graveyards in midnight mists is how people usually picture the rise of the dead. Bushy-beards and wonky wa-wa waves on a six-string, tie-dye twists and baby boomers lighting up, is however, the reality.

Far from the grave, ex-Grateful Dead frontman Bob Weir and his solo project RatDog, have scoured the sphere, playing over seven hundred shows since 2006. Along with a slew of brilliant musicians such as lead guitarist Mark Karan and keyboardist Jeff Chimenti, RatDog has dug deep into the core of improvisational riffs and melodies, and is safely the most musically comprehensive jam band formed post-sixties. A chunky brew of blues, jazz fusion, progressive bluegrass, and folk, RatDog delivers with an equally diverse palette as the latter day Grateful Dead. Weir channels Garcia in numbers like “Black Muddy River” and “Scarlet Begonias.” Yet the spectacle lies in the audience. The peace-loving, daisy-smelling youth that once swarmed Dead shows have become the stock-broking, suit wearing, SUV-driving dads, moms, and grandparents who come see Bob Weir to remember the days of freedom and hope, if just for a couple songs.

Maximum Ink: Musically and culturally, how do you define being relevant in today’s society?

Bob Weir: Making waves. And ripples. For me, it’s about the kind of response we get from the people we play for. And we’ve been getting a pretty solid response, so I guess that means we’re rollin.’

MI: How do crowds change over the years? Has it changed how you make music and perform?

Bob Weir: Well, actually kind of contrary, they haven’t much changed over the years and so we work within a continuum everything changes drastically, but what we do, our basic mode of operation, is to stay the same. What I mean when I say it hasn’t changed, is that we’re playing pretty much for the same age demographic that we’ve always played for., Our audiences, it’s about a 6-year period where they get older, then they get younger again and it kinda goes like that.

MI: Back in the Grateful Dead, you inspired much of the youth culture revolution of the ‘60s, do you think that sort of major shift can happen again? Or can Pandora’s Box only opened once per culture?

Bob Weir: What we had back in the 60s was a demographic pattern that has no repeated itself since. We had a huge preponderance of music in our country and the baby boom. And kids being characteristically a bit more open, and listen to waves and having a capacity for challenging authority, there was just a lot more of it going on at that time then there has been before or since. That’s not to say that we won’t get another baby boom, but it would take something like a major war or I think something like that to happen to recreate that baby boom.

MI: When you look at music history, a great majority of the all-hailing classics come from that time period.

Bob Weir: For me I was at the right place at the right time, really at the tip of that surge.

I think it was the amount of focus, once again the numbers, and the amount of focus that was brought to music of a certain genre that made all those timeless classics what they were.

MI: I read somewhere that you were an undiagnosed dyslexic which made school very difficult. Do you think you would have had a different legacy had school been easier?

Bob Weir: Ahhh. Probably not. Because like I said, I think I was about eight years old when I first learned to tune a radio, music was all I was really drawn to, it was all I ever wanted to do. I would challenge myself. It was and has always been a challenge for me to get up and sing in front of people, I’d get stage fright. But that said it’s all I ever wanted to do so I just bucked up and did it and just kept challenging myself more and more as bigger opportunities presented themselves.

MI: One of the most significant moves you made in the Grateful Dead was allowing the audience to tape shows. Was the possibility of getting ripped off important to you at the time?

Bob Weir: Well we didn’t feel it was going to inhibit our record sales at all and at the same time, we didn’t want to be cops and police the situation. Back then, people weren’t copying our records, but we would spend the time, effort, money, and energy to buckle down and make a record, that wasn’t what was being traded around. People were coming to our shows and taping our shows, and trading them around. Then when you spend all that time, effort, money, and extensive energy to make a record if you can’t get anything back from it, you take away the sales of that project. Why go into the studio, why put yourself to it if you can’t make a living doing that.

MI: What quality did the Grateful Dead possess that other bands of the time did not, allowed you to invest so much trust in your audiences, where other bands would not take such a risk?

Bob Weir: I’m not sure it is a risk that other bands can’t afford to take. Its just a matter of whether they say it that way. What it boils down to is like the line in the song Uncle John’s Band: “are you kind” and it’s a double entendre, where ‘kind’ refers to “Are you kin?” “Are you our kind of people,” and then “are you kind and generous?” and loving. Well we’re all kindred spirits and the band and the fans are all people who are in for a little adventure. (Pauses) We’re one and the same. Some of us make more noise and some of us do more listening.

MI: What about playing the blues is the most appealing to you?

Bob Weir: I don’t know if I’ll be able to put that into words. It’s just a feeling, and it’s a quintessentially American feeling.

MI: What emotions do you extract when playing the blues?

Bob Weir: There’s a fury about the blues. Even in the most beautiful songs, there’s a (laughs) the underlying notion that although things are looking bleak, somehow I’ll survive, ill endure. There’s something I guess revolutionary about it. It’s a matter of revolting against oppression, in particular, depression. You can be depressed for any number of reasons. A love interest lost or a social injustice being suffered, but nonetheless…For a moment while you’re performing it, you’re throwing off that hope. We’ve all got to get through something.

MI: More than anything, the blues are about storytelling, and as a blues artist, in order to make the music authentic, you must have to have stories in mind.

Bob Weir: Yes, definitely. Any artist is a storyteller. Whether you’re using paintbrushes or guitar picks, your painting a picture and telling a story. If you go see a Van Gogh, it roars at you, you can hear it, you can hear what its like to be on the fields with the wind blowing across the wavy fields of grain. You can hear the buzz of the stars in “Starry Night.” In the song “Summertime,” you can feel the hot breath of the summer. What I mean by story, it’s more than just a tale, and it’s an all-encompassing experience. When someone tells you a story, you feel it, you can hear it, see it, taste it, and smell it. The more complete a story is, the more completely it holds your senses.

MI: Storytelling through music is an ancient form that predates language. Is that legacy relevant to you?

Bob Weir: I feel it. When I’m onstage and engaged in telling a story I feel like I’m involved in something timeless, elemental, and profound.

• Wiki